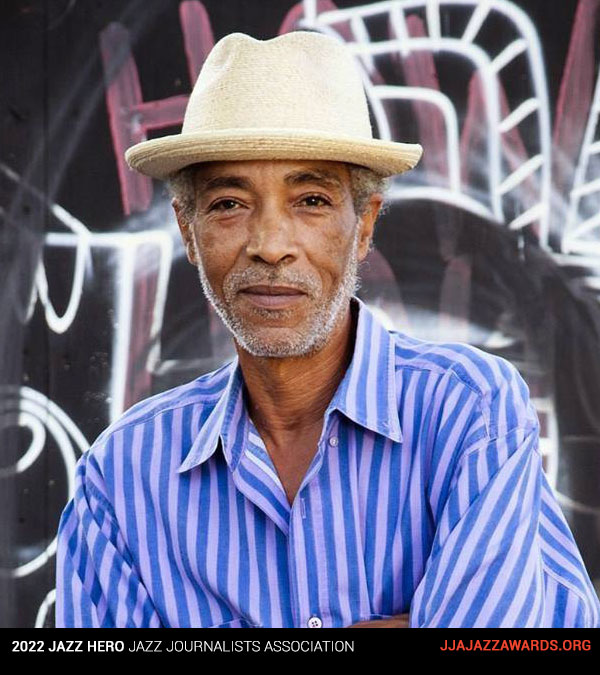

Austin Jazz Hero

For nearly three decades. Harold McMillan has presented jazz and blues music in a city that too often relegates historically Black music to the sidelines. He’s hosted several jazz festivals, including the Clarksville Jazz and Arts Festival/Austin Jazz and Arts Festival, has produced several touring shows by artists including Jimmy Smith, McCoy Tyner and Roy Hargrove, and also I’ll Be Home for Kwanzaa (Bagel, 1997), Austin’s only holiday recording featuring jazz, blues and gospel. Additionally, McMillan is a gifted musician, playing bass. But labeling him as a producer or artist overlooks his most significant contribution to the Austin jazz community: Cultural preservation.

To fully grasp McMillan’s significance to Austin’s music scene, one must understand the city’s history. In 1928, the city designated six square miles in Central East Austin as the Lone Star State’s sole Black cultural district. Dubbed the Six Square Cultural District, Black culture flourished there while segregated from the rest of the city and under constant threat of suppression. McMillan has been one of the most stalwart protectors of the District’s culture.

McMillan began preserving the East Austin musical community in 1990 with the Blues Family Tree Project, his effort to uncover and archive Austin’s history of Black artistry. That project led him to create DiverseArts Culture Works, a non-profit organization dedicated to the District’s long-term development.

In a role that combined his interests in preserving history and facilitating new music, McMillan became associate producer of the Historic Victory Grill. Founded in 1945, the Historic Victory Grill once presented a veritable powerhouse of Black artists from James Brown to Billie Holiday; it also started the career of Albert Lavada Durst, Texas’ first Black radio deejay. As decades passed and other venues closed, the Historic Victory Grill became the Chitlin’ Circuit’s sole survivor in the District. McMillan’s success there also gave rise to his outdoor performance venue, Kenny Dorham’s Backyard. Named after East Austin’s most famous jazz artist, it’s now another cultural institution.

But in a city whose population grew 30.09% over the last decade, far too many long-standing venues have been replaced by high-rise condos. Facing the threat of gentrification, in 2007 McMillan convinced the Austin City Council to create a preserved cultural district in East Austin. However, the enacted resolution was more symbolic than substantive. Consequently, McMillan created the East Austin Creative Coalition to push the Council to give the enactment teeth. The Coalition’s efforts led to a second City Council, resolution last fall which (in the words of the Austin Chronicle) “directs city staff to solicit plans and cost estimates for development of the ‘multi-story mixed-use development’” to be known as Kenny Dorham Center, with concert and rehearsal spaces, a recording studio, a museum and affordable housing for artists in an increasingly unaffordable metropolitan area.

While only time will tell what the new Center will accomplish in preserving and growing East Austin’s Black cultural legacy, one thing remains clear: If Austin is to be truthful to its title as “Live Music Capital of the World,” it must reflect all of its residents. Austin music is more than just Stevie Ray Vaughn and Willie Nelson — it is also Kenny Dorham and Austin Jazz Hero Harold McMillan. — Rob Shepherd